-

Hey, guest user. Hope you're enjoying NeoGAF! Have you considered registering for an account? Come join us and add your take to the daily discourse.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TolkienGAF |OT| The World is Ahead

- Thread starter Loxley

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

That's very interesting and an opinion I've come across before. A liking, even love for the Silmarillion, but regret at having read it. The small, often subtle allusions to the history of Middle-earth are some of the aspects (of The Lord of the Rings in particular) that really evoke something in people. Something of that is lost with exact knowledge of Middle-earth's history.I like the mysteries of the world.

This feeling of an old world that's itself almost a haunting ghost layered upon the real world. I regret having read the Silmarillion I think and knowing most of the history. It would have been great to have a few big Children of Hurin like books while keeping other parts still a mystery - like the fall of Numenor.

For me, I mainly love the sense of adventure and exploring and discovery.

Which, with Tolkien's marvelous way of describing things, is always a joy.

This is the same for me.

Also I like the comfy feeling when - for example in Lord of the Rings - he describes them in places such as Crickhollow, Prancing Pony, around a campfire, Lothlórien etc. That's when you feel most like part of the fellowship, like you're on the journey with them.

Examples in The Hobbit would be Bilbo's house at the start and Beorn's house.

Also I like the comfy feeling when - for example in Lord of the Rings - he describes them in places such as Crickhollow, Prancing Pony, around a campfire, Lothlórien etc. That's when you feel most like part of the fellowship, like you're on the journey with them.

Examples in The Hobbit would be Bilbo's house at the start and Beorn's house.

There are quite a few things I like about Tolkien's writing but this might just be my favorite element of it when reading his books.

Beren the Empty-Handed

Member

Well hello there.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

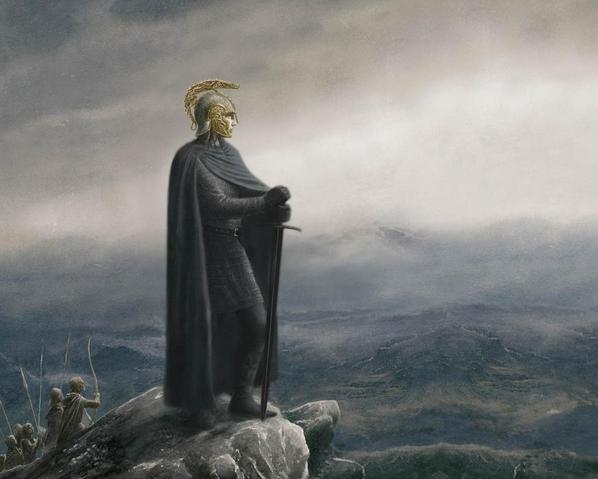

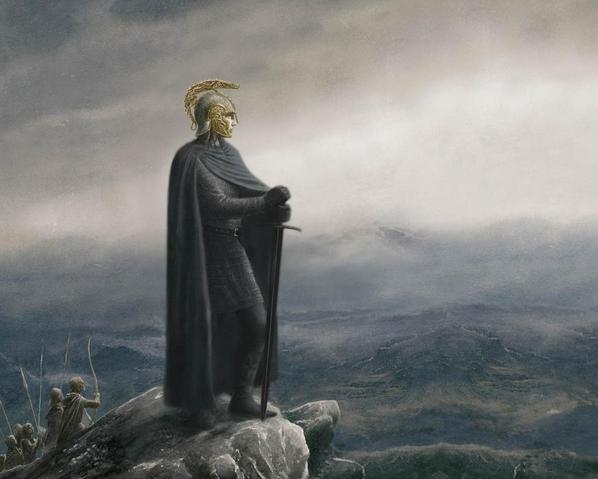

Two of Middle-earth's greatest warriors above. We're just missing Hurin from the Edain. And some Elves and Dwarves of course.

Pimplitosaurio

Member

This might be a stupid question, but I just finished reading the books again* and, why is Gandalf so mean to Pippin?

I mean, i get it in Moria, but if I recall correctly he disses Pippin other times just because. I think that I recall he saying something to Pippin when he meets him again in Isengard, i believe

*I have the books in spanish. I think I want to read them in english. Is the english version completely superior to the translation or only superior? do the songs/poems rhyme/make sense in english?

I mean, i get it in Moria, but if I recall correctly he disses Pippin other times just because. I think that I recall he saying something to Pippin when he meets him again in Isengard, i believe

*I have the books in spanish. I think I want to read them in english. Is the english version completely superior to the translation or only superior? do the songs/poems rhyme/make sense in english?

Suburban_Nooblet

Banned

Edmond Dantès;155846086 said:Two of Middle-earth's greatest warriors above. We're just missing Hurin from the Edain. And some Elves and Dwarves of course.

Edmond I have followed a lot of your posts concerningTolkien history, I do believe you are the go to expert on GAF for Tolkien.

Please correct if wrong.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

It's mostly frustration from Gandalf; having to deal with the quirks of a Took while carrying the burden of leadership. It's also the inherent grumpiness of his character as written by Tolkien.This might be a stupid question, but I just finished reading the books again* and, why is Gandalf so mean to Pippin?

I mean, i get it in Moria, but if I recall correctly he disses Pippin other times just because. I think that I recall he saying something to Pippin when he meets him again in Isengard, i believe

*I have the books in spanish. I think I want to read them in english. Is the english version completely superior to the translation or only superior? do the songs/poems rhyme/make sense in english?

In terms of the translations, some are quite well done, but there is a tendency for Tolkien's uniqueness to be lost in translation. I'd certainly recommend reading them in English. The poems in their native language will certainly be more appealing to you especially if read out aloud.

I'm regarded as a Tolkien scholar yes, but I'm just one of many who are passionate about Tolkien's works and specialise in this particular area of literature.Edmond I have followed a lot of your posts concerningTolkien history, I do believe you are the go to expert on GAF for Tolkien.

Please correct if wrong.

Think of me and Loxley as analogous to Gandalf and Aragorn. TolkienGAF is our Fellowship.

terrisus

Member

This is the same for me.

Also I like the comfy feeling when - for example in Lord of the Rings - he describes them in places such as Crickhollow, Prancing Pony, around a campfire, Lothlórien etc. That's when you feel most like part of the fellowship, like you're on the journey with them.

Examples in The Hobbit would be Bilbo's house at the start and Beorn's house.

Agreed, those are great as well. They feel like real places, where you could just walk in, sit down, relax, chat with the people, and live for a while.

Beren the Empty-Handed

Member

Its hard to give just one reason I fell in love with Eä. The depth of the mythos that creates the feeling of history is probably the best single reason.

I enjoy seeing the world today through the lens of "what if this was our real history?"

That was in part his goal when he was younger. He wanted to create a great mythology for Britain, since there is no great Britain mythology (you must remember that Arthurian legend as it's known today is largely a French invention).

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

A grand vision indeed, but ultimately he failed in his quest to give England a myth cycle on par with the Celtic and Welsh mythologies. The Silmarillion as he envisaged it is quite different to what Christopher had published in 1977.That was in part his goal when he was younger. He wanted to create a great mythology for Britain, since there is no great Britain mythology (you must remember that Arthurian legend as it's known today is largely a French invention).

Edmond Dantès;155938120 said:A grand vision indeed, but ultimately he failed in his quest to give England a myth cycle on par with the Celtic and Welsh mythologies. The Silmarillion as he envisaged it is quite different to what Christopher had published in 1977.

To be fair (and I'm sure you know this) JRRT had started removing many of the references to England as early as the 1920s. The published Silmarillion is surely very different from what would have been if Tolkien had ever finished it (though I'm not sure he could have), but the England stuff he'd already started moving away from himself.

WanderingWind

Mecklemore Is My Favorite Wrapper

Edmond Dantès;155938120 said:A grand vision indeed, but ultimately he failed in his quest to give England a myth cycle on par with the Celtic and Welsh mythologies. The Silmarillion as he envisaged it is quite different to what Christopher had published in 1977.

I would disagree somewhat. True, his creations are not seen as uniquely British, nor are they really considered mythology, but that latter is due almost exclusively to their relative newness. While it is true that he was not the first to create fantasy fiction, his works have basically become the blueprint for decades upon decades of movies, shows, plays, books, music, tabletop gaming and video games.

In terms of what would constitute a modern mythology, sans religious trappings, that's about it. Not to mention - and this is a point you know better than I - not every author has generated so much critical and scholarly study. Given enough time, I think our ancestors will certainly name his entire body of work a mythology in its own right, either eventually as a product of his native land or (more likely) as the progenitor of what we know today as fantasy...well, everything. We're just too close to the subject matter. Give it, oh, 2000 years or so.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

Indeed. One wonders how much of an effect the rejections of the Silmarillion material had on Tolkien and what changes it brought about in the material. The manuscripts he put forward for publication, which were subsequently rejected are the closest he ever came to 'finishing' his life's work. Although in one case it wasn't the material itself that was the reason for rejection, but simply not paying any heed to it.To be fair (and I'm sure you know this) JRRT had started removing many of the references to England as early as the 1920s. The published Silmarillion is surely very different from what would have been if Tolkien had ever finished it (though I'm not sure he could have), but the England stuff he'd already started moving away from himself.

I very much agree that time will favour Tolkien's Arda Cycle. Its sheer scope is enough to place it amongst the great mythologies of the world, yet alone its other favorable attributes.I would disagree somewhat. True, his creations are not seen as uniquely British, nor are they really considered mythology, but that latter is due almost exclusively to their relative newness. While it is true that he was not the first to create fantasy fiction, his works have basically become the blueprint for decades upon decades of movies, shows, plays, books, music, tabletop gaming and video games.

In terms of what would constitute a modern mythology, sans religious trappings, that's about it. Not to mention - and this is a point you know better than I - not every author has generated so much critical and scholarly study. Given enough time, I think our ancestors will certainly name his entire body of work a mythology in its own right, either eventually as a product of his native land or (more likely) as the progenitor of what we know today as fantasy...well, everything. We're just too close to the subject matter. Give it, oh, 2000 years or so.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

Christopher Tolkien was responsible for the maps in The Lord of the Rings under his father's guidance and Tolkien himself drew the Hobbit illustrations.I recently got my order of The Hobbit+LotR books, Pocket size. Thanks to TolkeinGAF for letting me know of it.

The books are really nice and I like that it has the maps along with some artwork, which I assume were by Tolkein or OKed by him?

tryagainlater

Member

Is The Children of Hurin worth getting if I've already read the story in Unfinished Tales?

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

If you've read the two versions found in The Unfinished Tales and The Silmarillion respectively, then you won't be missing much.Is The Children of Hurin worth getting if I've already read the story in Unfinished Tales?

I do however recommend the audio version narrated by Christopher Lee.

tryagainlater

Member

I'll have to check that out. I do love Christopher Lee's voice.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

You can listen to the whole book here:I'll have to check that out. I do love Christopher Lee's voice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMNAG9Mxkd0

I recently got my order of The Hobbit+LotR books, Pocket size. Thanks to TolkeinGAF for letting me know of it.

The books are really nice and I like that it has the maps along with some artwork, which I assume were by Tolkein or OKed by him?

As Dantes says, the maps were originally drawn by Christopher, who was his own worst critic about them, closely following his father's notes and sketches. This was long before Christopher edited The Silmarillion. Most modern editions have re-drawn maps, but they always follow Christopher's original closely. The only artwork LOTR that Tolkien was involved in were (iirc) were the original dust jackets, the door of Moria, and the color pages of the Book of Mazarbul, which are only found in the 50th Anniversary collector's edition.

I believe all the images in The Hobbit (excepting later re-illustrated images) were by JRRT himself.

Allen Lee did make some great artwork for Children of Hurin.

Oh heavens, I love the illustrations of Alan Lee and Ted Nasmith.

My hope is to one day have at least one of those illustrations hanging at my home. I'm very fond of this one in particular.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

Certainly up to his usual high standards.Allen Lee did make some great artwork for Children of Hurin.

The final image in particular captures the wretchedness of Hurin Thalion.

Question: In battle of the 5 armies what does thorin say when charging the orcs?

He's shouting "Du Bekár!", which (near as I can tell) is Khuzdul for "To arms!".

I like the mysteries of the world.

This is the same for me.

Also I like the comfy feeling when - for example in Lord of the Rings - he describes them in places such as Crickhollow, Prancing Pony, around a campfire, Lothlórien etc. That's when you feel most like part of the fellowship, like you're on the journey with them.

Examples in The Hobbit would be Bilbo's house at the start and Beorn's house.

There are quite a few things I like about Tolkien's writing but this might just be my favorite element of it when reading his books.

I've always enjoyed the darker elements of Tolkien's world. The Silmarillion expanded on some of that and gave us some striking imagery as well.

Its hard to give just one reason I fell in love with Eä. The depth of the mythos that creates the feeling of history is probably the best single reason.

I enjoy seeing the world today through the lens of "what if this was our real history?"

These all sum up what it is about Tolkien that I love so much. In general, it's the ridiculous world-building. Tolkien takes the time to go into so much detail that the Legendarium feels more tangible than any other fantasy universe I've come across.

Allen Lee did make some great artwork for Children of Hurin.

Man, I love Alan Lee and his style so damn much. I highly recommend his "The Lord of the Rings Sketchbook", which features hundreds of drawings he created for the LotR films. It's probably my favorite art book that I own. As someone who loves to draw with graphite, he's a huge inspiration.

tattooed_dwarf

Member

Can you tell me more about this, what did he exactly make and how much there is material on that books content?and the color pages of the Book of Mazarbul, which are only found in the 50th Anniversary collector's edition.

Can you tell me more about this, what did he exactly make and how much there is material on that books content?

Tolkien painted several pages (I don't have my copy with me at the moment but I think it was four) and then stressed/aged them to replicate the damage it sustained during the destruction of Balin's colony. The pages are all in runes, but some of it was translated by Gandalf reading from the book in the chapter "The Bridge of Khazad-dum". I'm sure people have transliterated the whole thing using the chart of runes found in LOTR Appendix E, but the text would presumably be in Khuzdul, which is poorly understood. You can find scans of these pages online too.

That would be the final page of the book, ending with the trailing off line of "They are coming".

Edit: see here too: http://andreas-lehr.com/blog/uploads/Lord_of_the_rings_50th_book_paintings.JPG

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

It's a testament to his dedication to giving his mythos an air of genuineness that he aged the paper. It was exhibited at the Bodleian Library a couple of years ago and is quite lovely in person. It almost passes off as a genuine historical manuscript.Tolkien painted several pages (I don't have my copy with me at the moment but I think it was four) and then stressed/aged them to replicate the damage it sustained during the destruction of Balin's colony. The pages are all in runes, but some of it was translated by Gandalf reading from the book in the chapter "The Bridge of Khazad-dum". I'm sure people have transliterated the whole thing using the chart of runes found in LOTR Appendix E, but the text would presumably be in Khuzdul, which is poorly understood. You can find scans of these pages online too.

That would be the final page of the book, ending with the trailing off line of "They are coming".

Edit: see here too: http://andreas-lehr.com/blog/uploads/Lord_of_the_rings_50th_book_paintings.JPG

CapitalismSucks DonkeyBalls

Banned

I don't know if anyone has read this yet, but Kotaku/io9 has an interesting article about the potential of East Middle Earth. A lot of this information is pretty basic to anyone who has spent just an hour perusing the beginning mythos of ME around the time of Morgoth. Still, it's a pretty interesting read.

http://observationdeck.io9.com/east-middle-earth-a-story-worth-telling-1691586234

Do you think we could see material from this side of ME come to the big screen anytime soon? Would it have have as great of an appeal as what we have already seen of Tolkien's world? I like the point the author of the article makes that a lot of the peoples of Eastern Middle Earth are interpreted as being of Slavic or Chinese descent and that might be less appealing to a general audience (whom had previously seen a majorly white cast).

http://observationdeck.io9.com/east-middle-earth-a-story-worth-telling-1691586234

Do you think we could see material from this side of ME come to the big screen anytime soon? Would it have have as great of an appeal as what we have already seen of Tolkien's world? I like the point the author of the article makes that a lot of the peoples of Eastern Middle Earth are interpreted as being of Slavic or Chinese descent and that might be less appealing to a general audience (whom had previously seen a majorly white cast).

Maybe I missed it in this thread or the OP, but what was the origin of Dragons in this series?

They were created by Morgoth, or rather they were corrupted/bred from earlier creatures, possibly Maiar. The earliest dragons had no wings, the first winged ones appeared at the very end of the First Age during the War of Wrath.

Do you think we could see material from this side of ME come to the big screen anytime soon? Would it have have as great of an appeal as what we have already seen of Tolkien's world? I like the point the author of the article makes that a lot of the peoples of Eastern Middle Earth are interpreted as being of Slavic or Chinese descent and that might be less appealing to a general audience (whom had previously seen a majorly white cast).

To be honest, I kinda hope not. We've got enough glorified fanfiction on our screens already and I don't trust Warner Bros or whoever with the IP. Not that I think it's likely though; because movie franchises are in the business of familiarity. I think the next onscreen Middle-earth projects are going to be set in the same regions we already know and recognize.

Edit: Variag is more of a job description than anything else. It doesn't make a ton of sense for them to be based on Vikings in any other ways.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

That's one topic that will be featured in the FAQs/featured posts that are coming soon.Maybe I missed it in this thread or the OP, but what was the origin of Dragons in this series?

Other hotly debated topics too.

Kyleripman

Member

For anyone who hasn't heard it, this radio adaptation of LOTR is simply superb. It features Ian Holm and Bill Nighy. Some of the performances (Gandalf, Sam, Gollum) are clear models for their eventual film counterparts. It's quite a commitment at 13 hours' runtime, but plug in your headphones at work if you can, and go on an awesome adventure. I just love this version.

Edit: I can't say enough good things about the performances in this. Gollum gives me chills.

Edit: I can't say enough good things about the performances in this. Gollum gives me chills.

For anyone who hasn't heard it, this radio adaptation of LOTR is simply superb. It features Ian Holm and Bill Nighy. Some of the performances (Gandalf, Sam, Gollum) are clear models for their eventual film counterparts. It's quite a commitment at 13 hours' runtime, but plug in your headphones at work if you can, and go on an awesome adventure. I just love this version.

Edit: I can't say enough good things about the performances in this. Gollum gives me chills.

Yep, the BBC Radio dramatisation is a classic.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

It's certainly the most faithful adaptation thus far. The Tales of the Perilous Realm by Brian Sibley and co is also rather good.

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

In Our Time radio show focusing on Beowulf

Last week’s In Our Time focused on the Old English poem Beowulf, and included many references to Tolkien’s scholarship and translation of the poem. You can listen to the programme for free: (subject to BBC regional restrictions):

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0542xt7#auto

Last week’s In Our Time focused on the Old English poem Beowulf, and included many references to Tolkien’s scholarship and translation of the poem. You can listen to the programme for free: (subject to BBC regional restrictions):

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0542xt7#auto

Melvyn Bragg and his guests discuss the epic poem Beowulf, one of the masterpieces of Anglo-Saxon literature. Composed in the early Middle Ages by an anonymous poet, the work tells the story of a Scandinavian hero whose feats include battles with the fearsome monster Grendel and a fire-breathing dragon. It survives in a single manuscript dating from around 1000 AD, and was almost completely unknown until its rediscovery in the nineteenth century. Since then it has been translated into modern English by writers including William Morris, JRR Tolkien and Seamus Heaney, and inspired poems, novels and films.

Tizoc

Member

EDIT: Wait hold up, did Gimli not know about the Balrog and the state of Moria? Reading up on the wiki that place must've been abandoned for centuries >_>

Interesting looking forward to it =)

Edmond Dantès;156170605 said:That's one topic that will be featured in the FAQs/featured posts that are coming soon.

Other hotly debated topics too.

Interesting looking forward to it =)

Edmond Dantès

Dantès the White

Yes, the featured posts should add to the thread and facilitate some good discussion.EDIT: Wait hold up, did Gimli not know about the Balrog and the state of Moria? Reading up on the wiki that place must've been abandoned for centuries >_>

Interesting looking forward to it =)

In terms of art:

The Fellowship by Vanderstelt Studio

http://store.vandersteltstudio.com/Gimli-the-Dwarf-Antique-Art-Print-Gimli-Antique-PG.htm

Only Gimli, Legolas, Merry and Pippin available thus far.

Gabriel_Logan

Member

Edmond Dantès;156405886 said:In Our Time radio show focusing on Beowulf

Last weeks In Our Time focused on the Old English poem Beowulf, and included many references to Tolkiens scholarship and translation of the poem. You can listen to the programme for free: (subject to BBC regional restrictions):

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0542xt7#auto

I will check this out later. I am still going through Tolkien's translation of Beowulf, though its slow going.

terrisus

Member

Holy shit...WHY IS THE FONT SIZE IN THE POCKET EDITION OF LOTR SO TINY?!

I need a friggin' microscope to read that lol.

Well I can read it normally but jeebus I wouldn't have minded if they were split into 2 part books long as the font size is as big as The Hobbit's.

I mean...

How do you think they got it to be pocket-sized? :þ

terrisus

Member

Imagine a pocket-sized Silmarillion - that almost sounds like an oxymoron.

What has it got in its pocketses?

Alrighty folks, time for our first featured post. We're starting off with part one of a three-part series of Tolkien FAQs that come from Gandalf himself - Edmond Dantès. Prepare for a knowledge bomb:

Tolkien FAQ Part 1 - by Edmond Dantès

Who was J.R.R Tolkien?

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, Englishman, scholar, and storyteller was born of English parents at Bloemfontein, South Africa on Jan. 3, 1892 and died in England on Sept. 2, 1973. His entire childhood was spent in England, to which the family returned permanently in 1896 upon the death of his father. He received his education at King Edward's School, St. Philip's Grammar School, and Oxford University. After graduating in 1915 he joined the British army and saw action in the Battle of the Somme. He was eventually discharged after spending most of 1917 in the hospital suffering from "trench fever". It was during this time that he began The Book of Lost Tales.

Tolkien was a scholar by profession. His academic positions were: staff member of the New English Dictionary (1918-20); Reader, later Professor of English Language at Leeds, 1920-25; Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford (1925-45); and Merton Professor of English Language and Literature (1945-59). His principal professional focus was the study of Anglo-Saxon (Old English) and its relation to linguistically similar languages (Old Norse, Old German, and Gothic), with special emphasis on the dialects of Mercia, that part of England in which he grew up and lived, but he was also interested in Middle English, especially the dialect used in the Ancrene Wisse (a twelfth century manuscript probably composed in western England). Moreover, Tolkien was an expert in the surviving literature written in these languages. Indeed, his unusual ability to simultaneously read the texts as linguistic sources and as literature gave him perspective into both aspects; this was once described as "his unique insight at once into the language of poetry and the poetry of language"

From an early age he had been fascinated by language, particularly the languages of Northern Europe, both ancient and modern. From this affinity for language came not only his profession but also his private hobby, the invention of languages. He was more generally drawn to the entire "Northern tradition", which inspired him to wide reading of its myths and epics and of those modern authors who were equally drawn to it, such as William Morris and George MacDonald. His broad knowledge inevitably led to the development of various opinions about Myth, its relation to language, and the importance of Stories, interests which were shared by his friend C.S. Lewis. All these various perspectives: language, the heroic tradition, and Myth and Story (and a very real and deeply-held belief in and devotion to Catholic Christianity) came together with stunning effect in his stories: first the legends of the Elder Days which served as background to his invented languages, and later his most famous works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Are Tolkien’s works racist?

Tolkien created a world where darkness exerts a gravitational force to which every race and individual is susceptible. What we must do is consider how race works as a literary device for investigating this important issue. Race operates analogously to character types in medieval works. It helped isolate certain characteristics for scrutiny and it also allowed him to play out general predispositions against individual choices, investigating the interplay of determinism and free will (fundamental aspects of the mythos). Of course the idea that racial predispositions can work as literary themes presents interesting problems. Let us examine some of the races. Tolkien wrote that Dwarves reminded him of Jews and he even employed Semitic phonemes in constructing their language. This may be construed as anti-Semitism, but Tolkien explicitly stated that this comparison was rooted in the experience of exile; Jews and Dwarves alike as essentially diasporic, simultaneously at home and foreign. It was a fascination for him, the idea of Dwarves in exile, laboring through an unwelcoming world against which their secrecy is a defense; driven from or attempting to return to ancestral homes. Further, when asked by a German firm in 1938 asking if he was of Aryan origin he wholly dismissed this; “I have many Jewish friends, and should regret giving any colour to the notion that I subscribed to the wholly pernicious and unscientific race-doctrine.” – Letter #29.

Elves incite explorations of artistic creativity and the fragility of art in a changing world. The Huorns and Ents speak for nature against the depredations of the other races and are certainly a fitting nemesis for often discussed iron fist of industrialisation. Men are the most variable of Tolkien’s races and through them he investigates weakness, love and mortality. There is no moral polarisation of men in Middle-earth, not only are many Numenoreans corruptible, but in The Two Towers, Sam even doubts the ‘evil’ motives of a slain Haradrim warrior, wondering “what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home.” An adaptation of this line was used in The Two Towers film; spoken by Faramir.

Thus we move onto Orcs (I place all varieties under this word) who expand on the consequences of tyranny. The mass production of hatred and the limiting of individual choice. Orcs are recognisably human and very little do they do that is outside the realm of human behaviour. Their actions throughout the mythos reinforce the Orcs’ kinship with humanity. Orcs are indeed depicted as ‘ugly’, but while their looks can be seen as an external metaphor for an internal condition, these are no more a fantasy characteristic than is Elven beauty. We can see ourselves idealised in the Elves. We see our shadow, the unadmitted, the worst side of human character in the vile but depressingly human behaviour of the Orcs and are thus forced to recognise it. Race is inconsequential, the exploration of the human condition at the fore.

Also of note is a rebuttal to the ‘civilisation against savages’ argument. The Orcs are representative of the industrialists that Tolkien was so wary of and the Children of Iluvatar representative of the Luddite ideal. To give but one example: the Goblins are established in The Hobbit as being capable of creating sophisticated machines far beyond the capabilities of mere savages and that is something on par with what the Numenoreans achieved. The theme of an advanced industrialist civilisation wreaking havoc on the more 'natural' way of life is a dominant theme and one that Tolkien was projecting when creating his mythos.

By refracting these issues through different races, Tolkien like medieval writers and scribes of ancient myth, risked flattening his characters into types; often described by critics as simple stereotypes. It can be equally said that Tolkien’s fascination with racial and cultural difference allowed him to explore the difficulty of understanding across cultural difference and the need for mutual respect. The Lord of the Rings places emphasis on the need for mutual respect and cooperation amongst the various peoples who coexist in Middle-earth and whose diverse cultures are threatened by the mono-cultural dominion of Melkor and Sauron.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This Tom Bombadil character: explain him to me.

"Who is Tom Bombadil?” asks Frodo fearing it a foolish question. Goldberry’s response of "He is” has led to much discussion for Tolkien fans. Some have equated “He is” to the biblical “I am” mistakenly equating Tom with Eru Iluvatar. Frodo also mistakes Golberry’s use of the word “Master” confusing it with power and domination.

Further on:

Frodo asks, "Then all this strange land belongs to him?”

Goldberry responds, "No indeed!” “The trees and the grasses and all things growing or living in the land belong each to themselves. Tom Bombadil is the Master".

Note that she actually doesn't explain what she means, but simple repeats the key word, "Master". Now we must turn to the Letters of Tolkien for some clarification.

"He is master in a peculiar way: he has no fear and no desire of possession or domination at all"

Clearly is seems that the philologist Tolkien is using the word in the sense of 'teacher' or 'authority', its original Latin usage. But that says what but not who and doesn't answer Frodo's question at all.

Further on, Frodo, trying to get a straight answer, asks Tom "Who are you Master?" . Tom frustratingly answers the question with a question:

"Don't you know my name yet? That's the only answer."

In the Letters (#153), Tolkien explained that:

"Goldberry and Tom are referring to the mystery of names."

At the Council of Elrond, the mystery deepens even more as Tom acquires more names that also say what, but not who he. The Men of the North call him 'Orald' (Old English for 'very ancient'). The Dwarves call him 'Forn', an Icelandic word meaning 'old', as in the ancient past. Elrond name for him is 'Iarwain Ben-adar', oldest and fatherless, which is a literal translation of Sindarin iarwain, 'old-young' and ben , 'without,' plus adar, 'father'.

All of these names essentially express the same idea, it seems that the additional names of Tom add only a common acknowledgment of age to our knowledge of who he is.

The 'is' from Goldberry's initial statement is the operative word. Tom as the oldest being comes before history and therefore cannot be related to or associated with anything but himself, his own existence. Tom Bombadil is pre-language and therefore not formed by language, saying of himself:

"Tom was here before the river and the trees; Tom remembers the first raindrop and the first acorn. He made the first paths before the Big People, and saw the little People arriving.... He knew the dark under the stars when it was fearless before the Dark Lord (Tom referring to Melkor here) came from Outside".

As with Väinämöinen, the eternal singer of the Kalevala (one of the key germs of inspiration for Tolkien), Tom is Arda's oldest sentient being. He is self begotten, fatherless, pre-existent. He simply 'is'.

The idea seems to be that there is an important connection between thing and word, and that each in a sense creates the other.

There are of course many theories as to who is, such as:

The theory claims that the Music of the Ainur is still prevalent in Arda and that Tom is an embodiement of it thus explaining his constant singing. It also details why Tom be regarded as the last if Sauron were victorious as the Music was the foundation of Arda and thus would be the only thing left if all came to ruin.

Or:

That Tom was a byproduct of the initial weaving of Arda when Melkor's discord directly opposed Eru's will. Melkor's theme took precedence the second time out of the three occasions hence Ungoliant was created (the very antithesis to light; the darkness that consumes light). Then Eru rebounded and his wrath was known to all the Ainu and his chords triumphed over Melkor's discord hence Tom was created (the antithesis of the dark; the light, incorruptible).

Tolkien himself said the following:

“As a story, I think it is good that there should be a lot of things unexplained (especially if an explanation actually exists) ... And even in a mythical Age there must be some enigmas, as there always are. Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally).”

“The story is cast in terms of a good side, and a bad side, beauty against ruthless ugliness, tyranny against kingship, moderated freedom against compulsion that has long lost any object save mere power, and so on; but both sides in some degree, conservative or destructive, want a measure of control. But if you have, as it were taken 'a vow of poverty', renounced control, and take delight in things for themselves without reference to yourself, watching, observing, and to some extent knowing, then the question of the rights and wrongs of power and control might become utterly meaningless to you, and the means of power quite valueless.”

“Tom represented Botany and Zoology (as sciences) and Poetry as opposed to Cattle-breeding and Agriculture and practicality.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Where did Tolkien get the word ‘hobbit’ from?

While there seems little doubt that he was telling the truth when he said he simply made it up, the issue was confused in the mid-1970s by the discovery, in a nineteenth-century collection of North Country folklore, of the word ‘hobbit’ among a list of faires, spirits, creatures from classical mythology, and other imaginary beings. The discovery was made by Katharine Briggs, the leading expert of her time on traditional fairy folklore who reprinted the list in her A Dictionary of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Briggs herself did not comment on the appearance of hobbits in the list, but her discovery was soon picked up on by an outside reader for the OED and thence reported in various newspapers (including most notably Philip Howard’s piece ‘Tracking the Hobbit Down to Earth’, which appeared in The Times on 31st May 1977), but for the most part without crediting Briggs for her role in the discovery. The list itself has appeared in a miscellany published by the Folklore Society, the full title of which was The Dehham Tracts: A Collection of Folklore by Michael Aislabie Denham, and reprinted from the original tracts and pamphlets printed by Mr Denham between 1846 and 1859. Edited by Dr James Hardy, this had been issued in two volumes in 1892 and 1895.

Despite its apparent plausibility, it is highly unlikely that the Denham Tracts was actually Tolkien’s source for The Hobbit. How then do you explain this coincidence? For one thing, English folklore traditions about ‘hobs’ played a part in Tolkien’s creation, including the name, and since this is the case it is not so surprising to find that Tolkien’s invention, his own personal variant, can be matched by actual example from historical record, albeit an obscure one.

Tolkien’s gift for nomenclature was posited on creating words that sounded like real ones, creating matches of sound and sense that felt as if they were actual words drawn from the vast body of lore that had somehow failed to be otherwise recorded. That his invention should match actual obscure historical words was inevitable provided he did his work well enough, as is also attested by the accidental resemblance of his place-name Gondor (inspired by the actual historic word ‘ond’ (stone), which had once been thought to be a fragment of a lost pre-IndoEuropean language of the British isles) to both the real world Gondar (a city in Northern Ethiopia, also sometimes spelled Gonder, once that country’s capital) and the imaginary Gondour (a utopia invented by Mark Twain in the story ‘The Curious Republic of Gondour). It is a tribute to Tolkien’s skill with word-building that his invented hobbit should prove to have indeed had a real-world predecessor, though Tolkien himself probably never knew of it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

What is Tolkien’s connection to Beowulf?

Beowulf’s text survives in a single manuscript copy in the British Library and is dated to about the year 1010. The circumstances of Beowulf’s composition are unknown and its date is not agreed, but there is evidence to suggest that it may have reached its present form before 850. Beowulf is a literary poem but many of its techniques originate in older oral traditions. It has more than three thousand lines and is the first large poem in English, even so, there is no reference to Britain. So one must ask, what its interest was for English hearers, some of whom had settled in Britain for as many as ten generations? Later audiences have found it a good story, but for its first audiences it was a good story about their ancestors.

Beowulf is the best known Old English poem, but there are others such as The Wanderer and The Seafarer. Compared with other narrative verse, Beowulf is considered richer and more elevated in style. As an epic it can be compared to Homer’s two great works. But it is more condensed and elegiac in tone than Homer’s poems, and is considerably closer to Virgil’s masterpiece; The Aeneid. Two things Beowulf does extremely well is show Old English poetic style and versification at their best.

But what of Tolkien and his feelings towards the unknown author (s) of the poem? Tolkien’s published comments make it clear that he felt a relationship with his completely anonymous and long dead predecessors, and much closer than one merely scholarly. In his lecture on the poem (above) Tolkien summed up generations of scholarship with the following words:

“Slowly with the rolling years the obvious (so often the last revelation of analytic study) has been discovered: that we have to deal with a poem by an Englishman using afresh ancient and largely traditional material.”

The description of the poet would be a fitting description of Tolkien. An Englishman certainly. For Tolkien was well aware that his surname had a German derivation (just as scholars of the past tried to make out that Beowulf was Frisian or Danish or indeed German); but he also knew that the derivation was centuries old (just like Beowulf), and insisted repeatedly that he felt himself to be an Englishman of the West Midlands, a Mercian.

As for using afresh ancient and largely traditional material, that is exactly the approach he took in creating his Legendarium, which he was at such pains to root in ancient, forgotten English tradition.

There are three major published analyses commenting on the poem, the 1936 lecture ‘Monsters and Critics’, the 1940 essay ‘On translating Beowulf’ and the posthumously published 1963 lectures under the name of ‘Finn and Hengest’ (1982). The 1936 lecture is accepted as the starting point for almost all modern criticism of Beowulf and is one of the most cited scholarly papers of all time. The 1940 essay is rarely cited and the 1982 publication has been all but forgotten. But this is very normal for Tolkien, only a few of his papers are regarded as field defining, the rest would have sunk without a trace, but for their connection to his fiction. Whether it be his writings on fairy stories, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Ancrene Wisse or Beowulf, what energized his scholarly writings was his close identification with the ancient writers who he passionately believed to have sprung from the same ground and talked the same language as himself and gave him a privileged insight into what they thought and what they meant. This identification was at its strongest with the unknown poet (s) of Beowulf.

Beowulf also had a key influence on some aspects of his fiction. To take just one example in detail. In The Two Towers, the approach and entrance of Aragorn and company into Meduseld follows the etiquette of Beowulf lines 229-405 almost exactly. The first challenge, leave taking by the first challenger, the second challenge by the warden of the door, the pilling of arms outside the hall, and the reception standing in front of the throne.

Not just etiquette, the name ‘Meduseld’ is merely a word from the poem at line 3065 (‘mon mid his magum meduseld buan’, translated to ‘to inhabit the mead-hall with one’s kin’that is capitalized by Tolkien. Edoras too is also formed by capitalizing a word in Beowulf from line 1037 and changing it slightly from its West Saxon form to a Mercian one, i.e. ‘in under eoderas; þara anum stod’.

Another aspect that Tolkien picked up from Beowulf aided him with the tricky issue of the Valar and his own personal beliefs. In the Book of Lost Tales when Tolkien first started writing about them, they seem more like the deities of the pagan Celtic or Norse pantheons. Although Tolkien did tone this similarity down in later life, because the appearance of such deities would contradict the First Commandment. By the time of the Silmarillion, they are firmly subordinate, angelic beings. Once again Tolkien found inspiration from the Beowulf poet (s). At the beginning of Beowulf, Scyld Scefing comes from over the waves to the Danish people in a miraculous manner, he reestablishes the kingdom and then dies. He is put in a boat laden with treasure by his people, who then entrust the boat to the waves, as if they expect him to return to whoever he came from. The poet says “this hoard was not less great than the gifts he had from those who at the outset had adventured him over the seas, alone, a small child” (lines 44-46). But who are ‘those’? No further clues are given and the poet even denies knowledge. The word þā, meaning ‘those’ in Old English is used 62 times in the poem, but it is only on this occasion in which it takes stress and alliteration. It could have been written as ‘He’ and ascribed as a miracle of god, but for whatever reason it is ascribed to an unknown group of beings, who possess supernatural powers, and who use them selectively and very occasionally for the benefit of mankind, just as the Valar do.

Many more examples of the influence of Beowulf can be discussed, ‘dragon-sickness’, the etymology of Saruman’s name and so forth, but to conclude, the relationship between Tolkien and the unknown poet (s) is much more than merely a scholarly one, but one that impelled Tolkien’s ambition to provide a mythology for his country.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.